Updated on 29 Jan 2012

| I’ve been reading a book this week called Learning SPARQL, shown at left. This book is an absolute steal in its Kindle edition. For less than 10 bucks, it provides a useful introduction into the world of RDF – Resource Description Framework.

This is a model for information that provides an incredibly flexible way to describe things and SPARQL is the query language that is used to get answers to questions about datasets that are expressed in RDF. The basic concept is the “triple”, which – expressed trivially – is a single fact about a thing.

So, for example, a fact might be that Ginger has red hair. |

And since a triple is made up of three (duh) parts, we can formally describe that fact as Subject=Ginger, Predicate=HairColor, and Object=Red. This is not in any known RDF format; it is just a simple way of illustrating the power of modeling data that way.

There is a related concept called “linked data”, which really just means that you can link datasets together by some common value. Much like databases and their foreign keys. But URLs are pretty much ubiquitous, since the World Wide Web uses them to hyperlink pages together. To steal a phrase from the book, it wouldn’t be much of a web without links.

And there are SPARQL end points that allow you to query data sets over the web and get results back in a requested format, e.g. HTML, RDF/XML, JSON, etc. Some pretty cool stuff in there.

And so we arrive at the earthquakes. To quote from Learning SPARQL:

Professor Jim Hendler and his Tetherless World Constellation group at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute converted a lot of the simpler data that they found through the US Data.gov project to RDF so that they could build semantic web applications around it. After seeing this work, US CIO Vivek Kundra appointed Hendler the “Internet Web Expert” for Data.gov.

DuCharme, Bob (2011-07-14). Learning SPARQL (p. 42). OReilly Media - A. Kindle Edition.

There is a lot of free data available on the Internet, it turns out. After reading this quote, I popped over to http://data.gov and found a menu that offered to let me explore some raw data.

Clicking on that menu item brings you to a list of datasets. I liked the first one on the list.

So I went there and found that I could download the dataset in a very familiar format – CSV.

This is, of course, a simple delimited text data format (comma separated in this case) that is presented in your browser like this:

Src,Eqid,Version,Datetime,Lat,Lon,Magnitude,Depth,NST,Region

nn,00366555,8,"Saturday, January 28, 2012 14:03:51 UTC",39.3858,

-119.9548,1.4,8.50,22,"Nevada"

ak,10399820,1,"Saturday, January 28, 2012 13:21:59 UTC",61.0241,

-152.2186,1.4,99.80,11,"Southern Alaska"

nn,00366553,8,"Saturday, January 28, 2012 13:12:18 UTC",38.2277,

-118.8112,1.2,18.70,10,"Nevada"

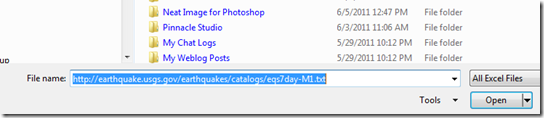

Interesting stuff, but not very useful in this form. So I copied the URL in the browser address area:

http://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/catalogs/eqs7day-M1.txt

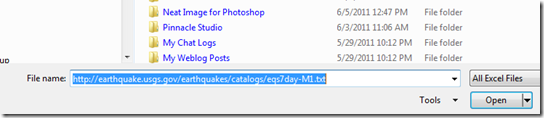

And pasted it into the file selection dialog of the open menu item for Excel 2007.

(You did know that you can use URLs in any most situations where you normally select local files, right?) When I do that, Excel recognizes the dataset format and asks me how it is delimited.

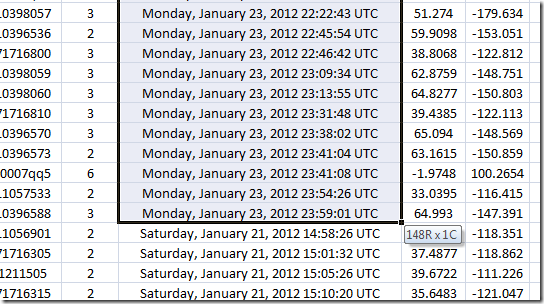

Selecting delimited and comma does the trick. It loads in a rather unpleasant format, obviously.

But I quickly got it into something more palatable.

So what can you do with these data sets in such a simple format? Well, quite a lot, actually. Some questions and their answers:

How many earthquakes were there world-wide in the last 7 days?

Subtract 1 for the header row and the answer is 1014. I’ll bet most people would not believe that number happens in a week, but it does.

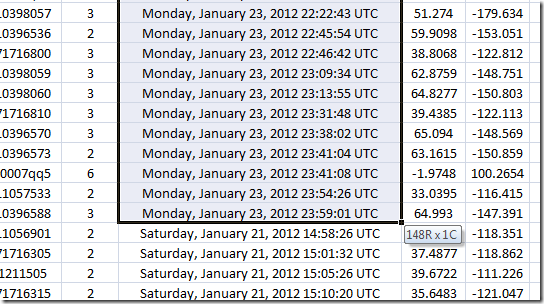

How many earthquakes were there last Monday, January 23rd?

After sorting, you select the first instance of the 23rd, scroll down, and while holding the shift key you select the last instance, thus selecting them all. You get the answer while holding the keys down:

148 rows means 148 earthquakes last Monday.

If you let go of the keys and that little tool tip disappeared, have no fear. The count is still visible for any selected area:

Note: There are much more sophisticated ways of exploring these data, even in Excel. I’m showing you brute force techniques so you can see how much information is expressed here without hiding it behind techniques with which you (or I) might not be familiar.

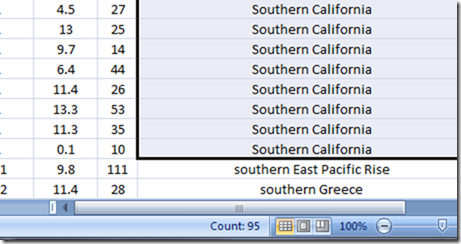

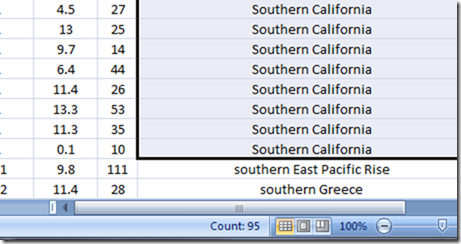

How many earthquakes occurred in Southern California last week?

That would be 95.

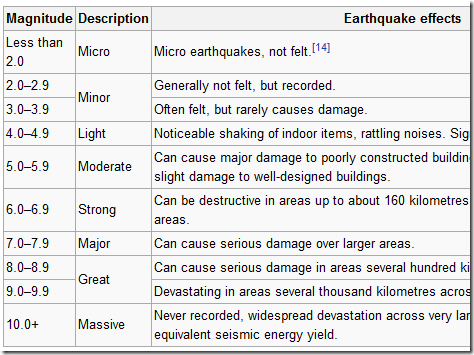

How many of those earthquakes were strong enough to be felt?

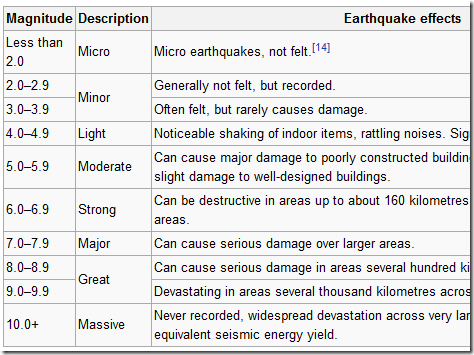

Here, we have to look up the Richter Scale to see what magnitudes can be felt.

Obviously, we must now search for all quakes magnitude 3.0 or greater. This gives as a list of the earthquakes that could have been felt, had someone been near enough the epicenter. If a tree falls …

Now, looking back at the sort I performed for the previous question, you will see that I also sorted in descending order by magnitude after I sorted by region. A method to my madness …

Looking at the dataset with that sort applied gives us the answer: zero. No one felt an earthquake in southern California last week because the highest recorded quake was magnitude 2.8. Of course, if one were standing right on top of the epicenter, that’s close enough that perhaps a slight tremor would be felt. But that’s not the point of the exercise. Pick your rules and query your data. The answers are accurate enough to be perfectly useful.

One final series of questions …

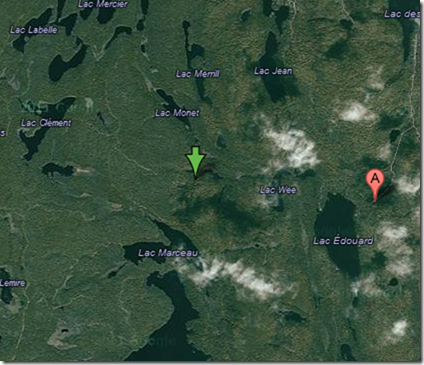

How many earthquakes were there in Canada last week?

Let’s use the search function to find all occurrences of Canada.

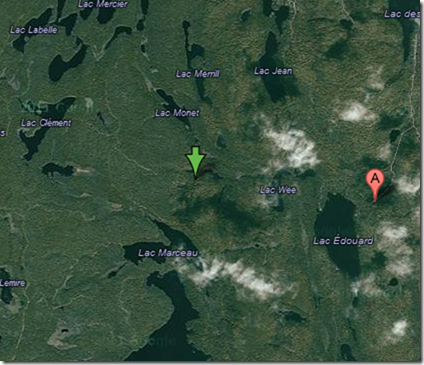

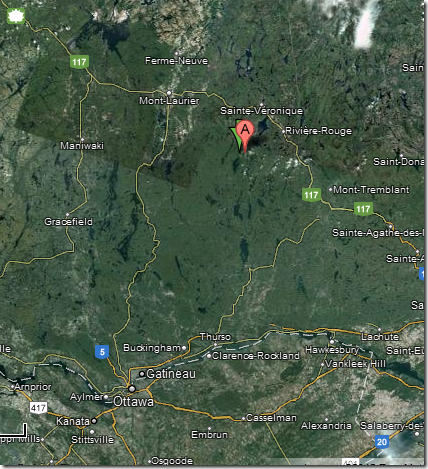

There was but one, in southern Quebec. Hey, that might be fairly close to where I live. Let’s just see how far away the epicenter was from me. Well, first let’s see where it was in the first place.

I tried the following trick without knowing whether it would work at all.

Copy the latitude and longitude and paste into Google maps:

It works! You get a point on the map showing the lat and long and you get the nearest address on a street or highway.

That’s very cool. We’re starting to extend the value of the data rather far. Let’s continue …

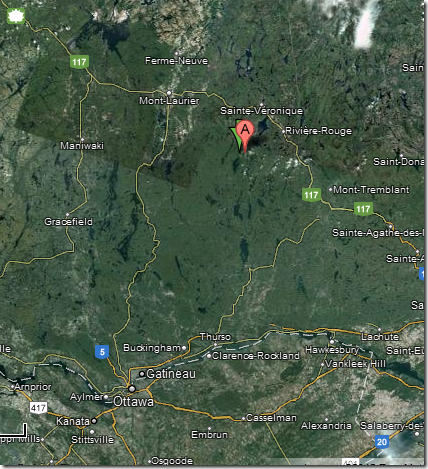

How far is that from Ottawa, approximately?

Not very …

Driving it is a little circuitous:

But that tells us that the approximate 200km distance is less than the directions say ot is by quite a bit …

As a 3.2 magnitude, those in cottages nearby should have felt it a little bit. But it was much too far away from Ottawa for any of us to have felt it.

Conclusion

This little brute force exploration of a simple dataset from the US government shows you just how much you can learn from poking around in this stuff. If you wanted to build up your own database for this information, and you had only Excel, you could download it each day, paste it into the master spread sheet, sort it and then tell Excel to eliminate duplicate lines.

Of course, the full dataset is probably sitting on the end of a SPARQL end point somewhere, just waiting to be queried. But the point is that there is tons of free data out there and you can do a whole lot without any sophisticated tools.

Have fun.

Addendum 1 – Distance from the quake to me

My friend Sue posted a couple of responses that contained the actual distance of the Canada earthquake from last week to my suburb. And that distance was a mere 126km, or 78 miles as the crow flies.

That’s not far at all. Still, I felt nothing, so it must be far enough to prevent even a gentle swaying from being noticed.

Her other response contained a superb link to a Google site containing the formulas and a calculator for distance between two points described by their Latitude and Longitude. Very cool.

http://www.ig.utexas.edu/outreach/googleearth/latlong.html

Addendum 2 – Of the 1014 earthquakes last week, how many were strong enough to be felt?

Ignore the datetime subsort … we won’t be using it and sorting alphabetically reverses the natural date order of Thursday and Friday for example :-)

Only 141. That’s fewer than I might have thought.